African-American History

African-American Interpretation

Research and Reveal the History of African and African-descended People in Salem

Explore Black History at Old Salem

Join us on Saturday, February 15 & 22, for Living Legacy Walking Tours and Spot Talks that highlight the lasting impact of Black artisans, foodways, and family legacies in Salem. These expert-led programs provide a deeper look at often-overlooked stories that shaped our community.

📅 February 15: African American Foodways in the Early South (Spot Talk with Bethany Kendall)

📅 February 22: Learning From Historical Black Memoirs to Shape New Family Histories (Spot Talk with Melinda Perrett)

📍 Spot Talks: 11:00 AM | Wachovia Room, Visitor Center

📍 Walking Tours: 1:30 PM | Meet at the Frank L. Horton Center

Included with Old Salem admission. No pre-registration required.

♿ Accessibility: Spot Talks are indoors. Walking tours cover about a mile on uneven streets.

Experience history where it happened.

To help as a research volunteer fill out an application! If you have any information, or you are a descendant of an enslaved individual, please email us at [email protected]

The Initiative

African born and derived people are among the founders and builders of Salem, and thus the city of Winston-Salem. Old Salem Museums & Gardens leads an initiative called the Hidden Town Project to research and reveal the history of enslaved and free people of African descent who once lived in Salem.

Through continued research, Old Salem is working to understand the history of all people who lived and worked in the town. Enslaved and free people of African descent participated in building the town, worked in the shops, industries, and homes of its white residents, and contributed to the general prosperity. Their descendants and the post-Emancipation African American population to the present-day are part of the story as well.

The history is complicated, and the research-based project is focused on identifying people and building their biographies, as well as understanding their lives within the white Moravian world. Community engagement is a critical component of the Hidden Town Project through collaboration, education, and public awareness. Understanding truth in history is basic to the conversation, as many people remain unaware of the history and the direct relationship of slavery — with its enduring legacy — to the profound inequities in our own time.

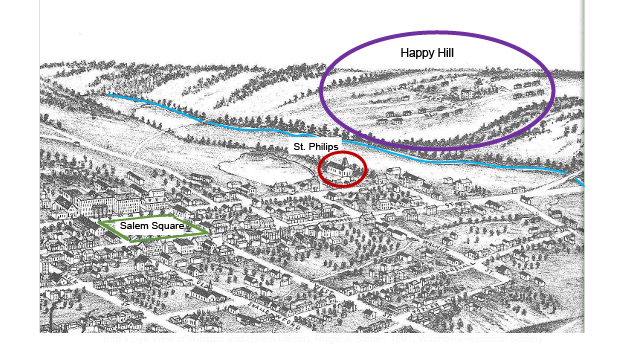

The project also seeks ways that Old Salem can better tell stories of people of African descent. Please visit the St. Philips African American Heritage Center or any other interpreted site at Old Salem to learn more about this history and the Hidden Town Project. If you would like to get involved in the Hidden Town Project, please contact us at [email protected].

St. Philips African American Heritage Center in Old Salem includes St. Philips Moravian Church (1861) — the oldest standing African American church in North Carolina – the Negro God’s Acre, and the reconstructed Log Church.

The Hidden Town Project was initiated in December 2016 with project goals to:

- locate sites of dwelling places of enslaved people throughout Salem

- fully integrate the narrative into the museum’s interpreted visitor experience

- connect with descendants

- archaeologically investigate designated sites

- interpret the heritage of people of African descent in Salem and their descendants through contemporary art forms, salon discussions, and public gatherings.

The initiative builds on previous work at Old Salem, beginning in the mid-1980s, and especially with the restoration of St. Philips Moravian Church (from 1989) and the accompanying discovery process through scholarship in the Moravian Archives and through archaeology. Two publications from that earlier work are available:

Landscape of Slavery

Understanding the landscape of slavery in Salem, broader Wachovia, and the individuals who were enslaved there, is essential. The detailed Moravian records provide insight and information about the people and the changing nature of slavery in Salem. The town’s theocratic leadership continually struggled to keep the number of enslaved people low through regulation of ownership; however, exceptions were made, and the renting of enslaved people was commonly approved. See “The Landscape of Slavery in Salem and Its Legacy.”

A small number of enslaved people chose conversion and became Moravians. Afro-Moravian Peter Oliver (1766-1810) was the only known Black Moravian householder in Salem. A communicant Moravian who was free in 1800, he married the free Christina Bass and leased a four-acre farm a few blocks north of Salem Square. Invisible under 200 years development, the farm site was located by the Hidden Town Project in February 2017 and is the future “Peter Oliver Pavilion Gallery,” a Creative Corridors Coalition initiative designed by Walter Hood.

During Peter Oliver’s life, the “integrated fellowship” between white and Black Moravians degraded, and he was one of the last persons of African descent buried in Salem’s God’s Acre. By 1816 the segregated Negro God’s Acre was established and in 1822, a Negro Congregation was started (the origin of St. Philips Moravian Church). The first church, a log building, was constructed adjacent to the new graveyard in 1823.

Although slave regulations prohibited ownership of enslaved people in town, farms grew up outside of town where the slave rules did not apply, including Kreuser’s and Schumann’s. By 1810 the Wachovia Plantation, also called the Negro Quarter, was established about 2 miles southeast of Salem Square. Founding church members Bodney (ca. 1756-1829) and Phoebe (ca .1771-1861) lived there with other church-owned enslaved people, and Bodney was the farm manager.

Dr. Schumann’s farm across Salem Creek grew to include seventeen enslaved people by 1836 when he decided to move into town where slave-owning rules prohibited his taking them. He manumitted Ceolia and her family, and they — plus an additional six free people (several related by marriage to Ceolia’s children) — immigrated to Liberia, with passage and settlement costs provided by Schumann. See “Schumann to Happy Hill”.

Acculturation and a changing economy toward industrialization challenged the slave regulations. Textile milling was a significant Salem industry, and enslaved people were used at the Fries mill. See “Threadbare No Longer”. Mid-19th century brought big changes. Forsyth County was created in 1849 with a new county seat soon named Winston (Salem and Winston grew side-by-side until the 1913 consolidation). In 1847 Salem’s slave rules were discarded as unenforceable, and the number of enslaved people owned by Salem residents increased until Emancipation in 1865. Not all Moravians were enslavers, but by 1860, the Federal Census recorded approximately 135 enslaved people in the town of Salem (Forsyth County’s total population of 12,692 included 1,766 enslaved people or 14%). Slavery in Salem was urban slavery, not plantation slavery, and especially after 1847, enslaved people stayed on their enslaver’s residential lot, either in the enslaver’s house or in an outbuilding.

A large new brick church was built in 1861 and called the African Church in Salem (St. Philips Moravian Church). Freedom was announced on May 21, 1865 in the church sanctuary. Following Emancipation, the segregated Freedmen’s neighborhood of “Happy Hill” was established and many formerly enslaved people in Salem became property owners there. African Americans also lived throughout the town of Salem in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. See “Black Settlement in Salem”. And although Black people had lived in Salem since the colonial period, by the 1930s, Jim Crow laws changed that. The area we know today as Old Salem became a segregated white neighborhood, and the Black presence became a “Hidden Town.”

Research

Who were the Africans and people of African descent in Salem?

The Hidden Town Research Program includes investigating Salem lots for full history which reveals associated enslaved people, and Biography files are created. However, enslaved people are not often named in the records, and much effort is made to identify people and make family connections. Research extends into genealogical information developed in 2002 by Mel White, Old Salem’s first Director of African American Programming. Documentation held by the Moravian Archives, including the “Diary of the Small Negro Congregation,” is invaluable.

As slavery in Salem evolved, it became generational slavery with enslaved family members scattered throughout the town and at other places in Wachovia. With complex dynamics, there is much yet to learn about relationships, but a start is made with over 200 identified people of African descent associated with slavery and its legacy in Salem.

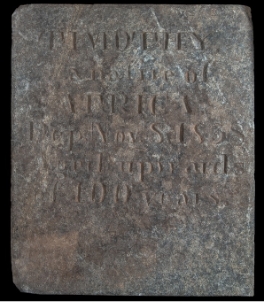

Connections to descendant populations are a significant project goal. Timothy (1736-1836) and Fanny (1749-1834) are a founding couple in the Wachovia area by the 1770s. Born in Africa, they were enslaved in Salem at the end of their lives. Timothy was over 100 years at death and Fanny was over 90. They were buried in the Negro God’s Acre, and their stories are told in the museum’s Log Church exhibit. They have many descendants today, including historian Spencer McCall who is working on a book about the family. His cousin, Lucretia Carter Berry, PhD, is an antiracism educator, author, and speaker who is co-founder of Brownicity: Many Hues, ONE Humanity. The family’s 82nd annual reunion included a special visit to Old Salem in August 2022.

The gravestones of Timothy and Fanny were among 31 grave markers discovered beneath the floor and behind the steps of St. Philips Moravian Church during early restoration work in the 1990s.

Genealogy is significant to understanding relationships. Old Salem’s Hidden Town Project is a member of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (AAHGS), NC Piedmont-Triad Chapter, and supports genealogical study to broaden understanding of history and human relationships. Old Salem sponsored a genealogy workshop by AAHGS president Lamar DeLoatch: “Migration Patterns”, and Hidden Town hosted the AAHGS Black History Month Conference in 2019. Hidden Town Project Community Research Fellow Jonathan Serrano co-presented with Martha Hartley at the 2021 Black History Month Genealogy Conference with “Genealogy Reveals Meaning for a Museum and for a Community.”

Where did enslaved people live in Salem?

There are no extant “slave houses” in Old Salem and locating the sites of dwelling places of enslaved people and investigating them archaeologically are research goals. Research Lot Files are being created to address this question, with interns and volunteers invaluable to the process. A set of primary and secondary sources are reviewed and gleaned for information about select Salem lots. An analysis is then made to describe the probable location of the “slave house.” To date, over thirty Salem lots have been researched.

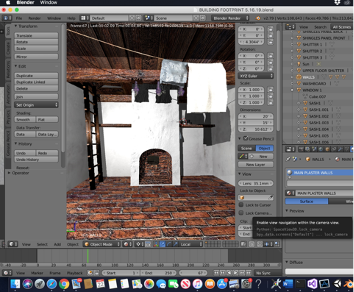

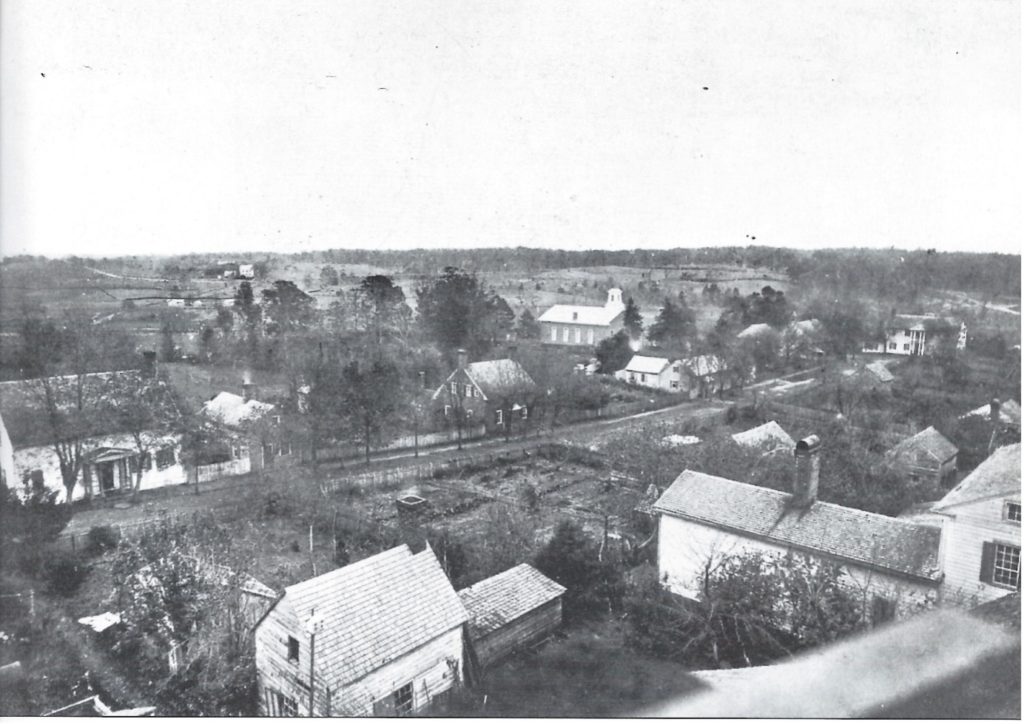

The basis for locating “slave houses” is the 1860 “Slave Schedule” for the Salem District, Federal Census for Forsyth County which enumerated “slaves” and “slave houses” by enslaver. Indications are that what was counted as a “slave house” by the census taker in 1860 was in most cases a building with another primary use (wash house, kitchen, workshop, etc.). The Hidden Town Project supported a 2019 master’s thesis by Dana Johnson, Savannah School of Art and Design, which created a virtual interior of a wash house or laundry that once stood on Lot 22 and is thought to have been the “slave house” enumerated in 1860, see images below. The laundry building is shown in the foreground of the ca. 1865 photograph of Salem.

Examples of a virtual reality experience for the laundry interior, including photogrammetry of Old Salem artifacts, created by Dana Johnson.

Christian David was a notable exception for an enslaved person. Although long-gone, a house was built for him in 1835 on Lot 7 by the church, and there may be other such examples. Virtual interpretation is a potential means of conveying invisible information at Old Salem (lost buildings and landscape). Collaboration with Middle Tennessee State University has produced AR modeling of the Christian David house and artifacts through Hidden Town in 3D.

Also of consideration is that some Salem residents who were enslavers and recorded with a “slave house” were farming, which brings the possibility of the “slave house” being located on the farm acreage and not in town. Further research is necessary. In addition, some enslaved people lived within the enslaver’s home in Salem, and research seeks to determine where in the house the enslaved people may have stayed.

North Carolina State University’s Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences conducted three days of Archaeological Geophysics (Ground Penetrating Radar and Electromagnetic Induction) in 2018. Two lots were examined, including Lot 67 (Blum) where a detached kitchen (no longer standing) may have been used as a “slave house.” That location, as well as much of the lot, was investigated. The geophysical examination is a preliminary step to archaeological excavation.

NCSU team conducted Archaeological Geophysics on Lot 67 in Old Salem. It is speculated that an enumerated “slave house” may have been a kitchen building once located in the rear yard.

Community Engagement

The post-Emancipation landscape of freedom included the first African American neighborhood in Winston-Salem: Happy Hill, and the Hidden Town Project supports efforts to revitalize this historic neighborhood.

In 1872 on the former Schumann farm across Salem Creek from the town, the Moravian Church created a segregated planned neighborhood for Freedmen with lots available for $10 each. Named “Liberia,” it was soon called Happy Hill, and by the 1920s about 130 families lived on the beautiful rolling landscape there. Residents crossed Salem Creek to travel to their workplaces in town, including tobacco factories, mills, other industries, and white households. Salem Academy and College was also a employer of many Happy Hill residents. Salem alumnae Jessi Bowman created a Storymap about the Happy Hill-Salem Academy and College relationship for her UNCG capstone with the Hidden Town Project. The content is part of the Anna Maria Samuel Project: Race, Remembrance, and Reconciliation.

For a century, beginning in 1910, neighborhood stability was upended by public policy decisions, which traumatized Happy Hill residents and their land, especially through a railway corridor, highway developments, and urban renewal. See highway impacts in “Hidden Town Project,” in Magnolia of Southern Garden History Society.

The Hidden Town Project supports revitalization of Happy Hill. The landmark 1998 Old Salem exhibit “Across the Creek from Salem: The Story of Happy Hill, 1816-1952,” brought together history, photographs, stories, and memories of the people of Happy Hill. A revival of the exhibit is installed at the Old Salem Visitor Center and is dedicated to Mel White, who led the collection of oral history and photographs in the 1990s.

The Happy Hill Neighborhood Association (HHNA) is focused on collaborative energy to foster renewal through recognition of history as well as arts programming, community gardening, and strategic planning. Significant efforts led by Triad Cultural Arts, Inc. (TCA) celebrate culture and architectural heritage through the Shotgun House Project. Old Salem regularly collaborates with HHNA and TCA. Hidden Town Community Research Fellow Brian Bonner participated in the successful application for a City of Winston-Salem Historic Marker for Happy Hill Cemetery, which will be installed in 2024.

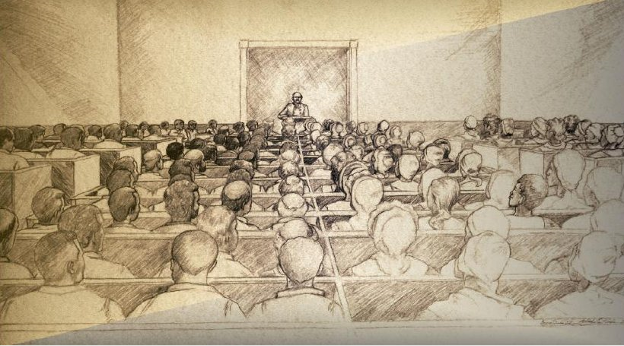

Public awareness and education of local history are key elements of outreach by the Hidden Town Project. Lectures are presented in public forums and to community groups, businesses, and students. Hidden Town is also a member of the Truth, Re/Conciliation, Reparations of Forsyth County, working to build an understanding of history, its impacts, and the way forward.

Recognizing that we live our history, we cannot limit ourselves to the historical record but use its insights to repair past wrongs and to move forward in human relationship.

Research Support

Since 2018, the Hidden Town Research Program has benefitted from volunteers and interns. Moye Lowe is a long-time research volunteer; Kelly Dixon and CJ Idol have also volunteered. Local college and university students have contributed much through semester internships as they learn through using primary source documentation to build research files. Students have included: Wake Forest University undergraduates – Abby Eakle, Ethan Wearner, Gabby Valencia, Robert Lyon, Maddie Douglas, Isabelle Merrifield, Carrie Lowe, Carolina Gonzalez-Gutierrez, Andie Coffey, Emily Dau, Bobby Farnham, Maddy Wagner, Leah Zuberer, Ella Bishop, Alyssa Walton, Gretchen Boyles, Matthew Capps, Meredith Groce, Kendall John, Robby Outland, Emma Grace Sprinkle, Garrett Toombs, Emily Wilmink, Madison Zehmer; Salem College undergraduates – Molly Sutphin, Jordan Wallen, Jessi Bowman, Kelly Dixon, and Salem Academy student Michaela Michael; UNCG graduate students Jessi Bowman, Katie Lowe, Sarah Grahl; and Savannah College of Art and Design graduate student Dana Johnson.